Fairy rings – fact and fable

Few people today would admit that they believe in fairies, but the problem of fairy rings are very much a reality.

Few people today would admit that they believe in fairies, but the problem of fairy rings are very much a reality.

Fairy rings have intrigued man for centuries, stimulating in him the desire for understanding. The curious scar which magically appears in fields and meadows, often perfectly round in shape and sometimes decorated with toadstools, has been written about by such notable poets as Shakespeare, Pope, Tennyson and Kipling.

The distribution of fairy rings, which is almost as ubiquitous as grass, is reflected by historical writings of many cultures in richly embroidered explanations of their origin. The most popular account, that of fairies trampling the grass in circular dances, may be found in the folk lore of many nations. In some accounts the toadstools provide shelter or obstacles for the dance and in others they are "suitable seats for musicians or tired dancers"!

The ring of bare soil, which is often seen between a band of darker green grass, has been attributed to a variety of causes worldwide. In Germany the bare rings were produced by witches performing a ritual dance on Walpurgis Night (April 30th/May 1st) whilst, in the Tyrol, a winged dragon passing over a field at the epoch of Pegasids (10th August) and Martinmas (11th November) branded the grass with its fiery tail.

The Dutch meanwhile recognised the marks of evil in these rings, attributing them to places where the devil, in resting his churn, burned the turf. Blemishes which were caused by the Lord of Darkness would not recover as quickly as those produced by natural fire and hence they were observed to take up to seven years to depart.

Scientists as early as the sixteenth century put forward the hypothesis that fairy rings were caused by lightning. Some exponents of the lightning theory go to great lengths to explain how the geometrical considerations of electromagnetic physics, relating to an electrical discharge of this type, cause the turf to be burned more on the perimeter than in the centre. Others took pains to explain how the variations in the size of the ring marks arise.

Bradley in 1789 describes two causes of the fairy ring phenomenon. The bare earth was a path made by burrowing ants which "flung up soil extremely fine" resulting in the improved vigour of grass in the immediate vicinity. He goes on to describe the ring of slime left by slugs and garden snails which go over the same ground at least twenty times in circular courtship. When this slime putrefied it gave rise to the ring of toadstools.

The zone of stimulated grass growth that we often see in some fairy rings is the subject of yet more postulation. Before the introduction of inorganic fertilisers one of the methods which a gardener or farmer would employ to improve the fertility of the soil was to apply an appropriate manure. It is therefore not surprising in writings of this era to find reference to various animals as the cause of this ring of luxuriant growth. Such animals as fallow deer, moles, rabbits, cows and goats were observed to adopt circular patterns of behaviour during courtship or play. The deposition of dung and urine during the course of these events was presumed even and consistent enough to produce the observed effect.

Superstitions relating to luck vary from different sources and are often contradictory. For example, to step inside a fairy ring can bring good or bad luck depending on your source of information. To have fairy rings in a field near your house was said to bring good fortune but, where two rings joined together, brought bad luck to the area. The dew from the darker grass of the fairy ring was much prized as a cosmetic skin treatment for a maiden's complexion. It was also used as an ingredient for a love potion.

A gentleman by the name of William Withering (1792) was the first to recognise the true cause of fairy rings to be fungal in origin and, so, once his ideas became accepted, the romantic age of fairies dancing in moonlit meadows began to fade into the mists of children's bed-time stories. He described one particular fungus Agaricus oreades.

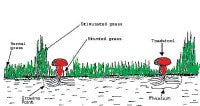

Today, we have identified a great many different species that give rise to fairy rings. The rings themselves are found to occur in three distinct types according to the effects that they have on the turf.

The first type of ring has a circle of dead or dying grass inside a larger band of darker grass. In the UK type 1 fairy rings are mainly caused by Marasmius oreades. The toadstools or 'caps' of M. oreades are mostly produced within the dead grass area and are reddish tan to buff in colour depending on the soil conditions and other environmental factors. Unlike many other large fungi, caps of M. oreades can withstand long periods of desiccation and, providing they are not disturbed, will re-hydrate when moist weather returns and continue their life cycle.

The ring of dead or dying grass results from the production of a toxin by the fungal mycelium in the root zone of the turf. The poisoning effect of this toxin is compounded by water stress caused by the presence of the ring of waxy mycelium that can be found just below the soil in the dead area. This thick layer of mycelium presents an impervious barrier that prevents the grass from getting sufficient water. The fungus lives off organic matter which it breaks down for food but, in doing so, releases nitrogen into the surrounding soil in the form of nitrates and ammonia. This has the effect of producing stimulated grass growth in the area adjacent to the fungus.

The subterranean mycelium advances away from the centre of the ring by six to eighteen inches or more each year. By studying aerial photographs it is possible to estimate the age of fairy rings. In Colorado, rings were reckoned to be 250 - 400 years old, and one in Belfort (France) was found to be about 700 years old, being one quarter of a mile in diameter!

The second type of fairy ring produces a ring of stimulated grass growth in which toadstools or puffballs can be found at certain times of the year. Although this is not as damaging as the type 1 ring, since it does not kill the grass, it is still a disfiguring scar on an area of close mown fine turf such as golf or bowling greens. The dark bands, or ribbons as they are sometimes known, are more evident in long hot dry summers when the surroun ding grass tends to lack colour.

ding grass tends to lack colour.

The third type of fairy ring has only a circle of toadstools or puffballs, without having a stimulated or a dead area. Also included in this category are those ring forming fungi that are found in woodlands. Type 3 fairy rings are easy to live with as the symptoms can be removed by mowing.Picture right Type 1 Fairy Ring

Type 1 and 2 fairy rings are not easy diseases to control because of their position within the soil, and the fact that they can be found as deep as 30cm below the soil surface.

Many attempts have been made to eradicate fairy rings and greenkeepers and groundsmen often have their own particular remedy. In the past the practice of manuring the bare areas of rings has been tried as it was thought that they were the result of some nutritional deficiency.

Many chemical methods have been tried with varying degrees of success including the use of fungicides based on Cadmium and Mercury. Soil treatment with methyl bromide gas and formaldehyde have also been tried. In the early 1980s Oxycarboxin was launched as the product 'Ringmaster', and proved useful in controlling type 1 rings, but the type 2 ring usually needed several applications to completely remove them.

Many chemical methods have been tried with varying degrees of success including the use of fungicides based on Cadmium and Mercury. Soil treatment with methyl bromide gas and formaldehyde have also been tried. In the early 1980s Oxycarboxin was launched as the product 'Ringmaster', and proved useful in controlling type 1 rings, but the type 2 ring usually needed several applications to completely remove them.

Ringmaster was followed by 'Fairy Ring Destroyer' containing the fungicide triforine, and by 'Mascot Clearing' a formulation of benodanil. Today, all of these products have been withdrawn from sale and the only recommendation for fairy ring control with a fungicide is on the 'Heritage' label. However, at present, this is backed by limited trials data on type 2 rings only. Picture left Type 2 Fairy Ring

The main problem with type 1 fairy ring is finding a way of penetrating the waxy mycelium that forms an impervious barrier to most materials. One method of control claimed to have some level of success is to apply daily heavy irrigation to the whole area occupied by the ring. This has to be carried out for at least a month. Unfortunately, whilst drowning the fairy ring fungus, the resultant waterlogging can create other problems by washing away the soil nutrients and encouraging moss and other fungal diseases.

Some people have tried using surfactants to break up and disperse the rings. One such product 'Clearing' (not to be confused with 'Mascot Clearing' - now withdrawn) is aimed at this method and contains soil penetrating surfactants suitable for use on all types of fairy ring as well as superficial fairy ring (thatch fungus).

An old method described by the Sports Turf Research Institute, in their booklet on turf diseases (circa 1975), was also reported to give successful control but, because it demanded a high input of labour, it was a very costly operation. Picture right Type 3 Fairy Ring

it demanded a high input of labour, it was a very costly operation. Picture right Type 3 Fairy Ring

By this method the turf in the infected area is removed and the soil below is dug over and treated with a drench of formaldehyde and a wetting agent. Great care has to be taken to avoid scorching the surrounding healthy turf with the formaldehyde or contaminating it with infected soil. The treated area is covered for 7-10 days with polythene to 'sterilise' the infected soil with the formaldehyde vapours.

After further digging the site must be left exposed for a period of two weeks to allow the solvent vapour to disperse before the surface levels can be reinstated and the site reseeded or turfed. Apart from the obvious cost in labour there was also the hidden cost in sports turf areas of providing an alternative playing surface while treatment is carried out.

Whichever way you look at it the problem will not go away - unless, of course you believe in magic!

Heritage is a trademark of Syngenta.

Clearing is a trademark of Vitax Ltd.

By Graham Paul