Generic or Branded?

I would hazard a guess that many of you, at some stage, may have made a visit to the medicine cupboard for an Aspirin®. And, with the careers that we have chosen, many of you have, at some stage, had to 'Roundup®' your weeds.

However, how many of you actually do use Aspirin for that troublesome headache or actually used Roundup for weed control?

A brief look in my medicine cabinet shows no aspirin but, instead, a product called Disprin® which, the packet informs me, is a generic form of aspirin. When I talk to the majority of turf managers about Roundup they say that they use a generic as "it's the same stuff only cheaper". Is this true, and what factors influence this purchasing behaviour?

The simplest way to define a generic pesticide is as one which is manufactured by a company other than the original manufacturer, whilst a generic manufacturer is "a company, or division of a company, whose major activity consists of manufacturing the active substances of pesticides, the patents for which have expired, and for which it did not hold the original patents".

In 1996, patent-protected active substances accounted for 47% of the total global agrochemical market, with up to 60% of the herbicide market comprising generics.

In terms of size, the biggest generic producer is the Israeli company Makhteshim-Agan, who partly own Farmoz in Australia. Its sales bring it into the top twenty agrochemical companies world-wide, and sales are rising faster than any of the leading R&D led companies.

Other major companies are the US Griffin, which recently formed a 50-50 joint venture with Du Pont, and the Danish company Cheminova Agro, who own a share of Ospray in Australia and recently acquired a large Indian company. Chinese and Indian companies remain a major and growing force in the generic market.

In recent years, there has been a proliferation of generic pesticides in the turfcare market, look-alike products with different commercial names but the same active ingredient, which is the component responsible for its ability to control the target pest. Generic herbicides are the fastest growing sector in crop production chemicals, but will they work well for you and save you money?

Registered agricultural and turf products are priced to include the cost of the testing and registration process, and it's this that provides assurance of quality and efficacy. Registered turf chemicals have passed a rigorous testing programme that ensures they are suitable for use and, when used according to the label instructions, manufacturers of registered chemical products provide a warranty.

In the USA, in order to receive Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) registration, a post-patent product must have the same technical merit as the current manufacturer branded product. The active ingredient must be the same technical material, which might be produced by the branded manufacturer or another manufacturer.

The same is true of solvents and inert ingredients. All generic products must pass rigorous EPA review and approval. If the formula changes from the originally branded product, those changes must get approval before it is registered. If anything in the formulation differs, the changes must have gained the approval of the EPA for the off-patent product to be registered.

Chlorothalonil and iprodione are among the chemistries that have been off patent long enough in different generic formulations to establish a good track record, and many superintendents are happy with their respective performances.

The main reason for the proliferation of look-alike products is the expiration of patents. In the USA agricultural chemical formulations are patented for seventeen years whilst, in Australia, this period is now eight years data protection. During those years, only the company that has developed the product is allowed to produce and commercialise it. After that period, any company can synthesise the herbicide and commercialise it under a different name.

However, the decision to market an off-patent chemical is not that simple for three reasons. Firstly, the original manufacturer can lower the market pricing of the branded product, therefore making it difficult to compete.

The second reason as to whether or not to go to market is that the original manufacturer might have been successful in developing an improved formulation that is now under patent protection and makes the original chemistry inferior. This is the case with propiconazole (Banner Turf (250g/L), now marketed as Banner Maxx (144g/L) (Syngenta).

The third obstacle to marketing an off-patent product is cost. While generic products offer price advantages, market experience shows that they are only able to capture between 10-30% of the market.

However, assuming a generic manufacturer decides to enter the marketplace, the key, and major driver influencing any purchase, is their cheaper price. As generic manufacturers do not pay the cost of developing the herbicide, they are able to sell the generic products cheaper than the brand name alternative.

Regardless of what company makes the herbicide, the core issue is whether generic herbicides are as good as brand-name ones.

Both generic and original branded products have the same active ingredients. Therefore, generic and brand name herbicides should have the same performance. However, generic and brand name pesticides are not required to have the same inactive ingredients.

In the case, for example, of soil applied herbicides the inactive ingredients would only influence handling and mixing properties of the formulation. therefore, actual performance in the soil should not be affected.

How well the product sticks to the leaf surfaces, as well as other factors, are where the composition of the inactive ingredients (solvents, stabilisers, emulsifiers, surfactants and other additives) of post emergent products can have a broader influence.

These additives can make a difference in the performance of the product you are buying, and are usually listed on the label as inert ingredients with no additional information revealed to the buyer. Nevertheless, products are extensively tested before release, and differences should be minimal, unless one of the inactive ingredients is missing altogether.

Another difference between generic and brand name herbicides could be the physical form of the active ingredient.

Glyphosate, the active ingredient of Roundup, has a host of generic versions on the market and these may differ in chemical form, i.e. potassium, di-ammonium, or mono-ammonium salts. Nevertheless, several studies showed that only minor differences were observed between the glyphosate formulations and these differences were, most likely, due to variations in the weed populations from plot to plot.

In conclusion, generic products tend to perform as good as their brand-names counterparts, provided that they have the same inactive ingredients and isomer structure. When evaluating whether generic products fit your business, you should compare their cost, safety and relative performance.

Gannon and Yelverton (2007) looked at the question of generic plant growth regulators and herbicides to see how they compared.

Cost, efficacy and potential formulation issues were all examined from the turf managers perspective. A number of branded and generic products were tested but, of specific relevance due to familiarity to the Australian turf manager were oxadiazon, quinclorac and trinexapac ethyl. The end conclusion was that, for all the products tested, there was no significant difference in these products from the perspective of both efficacy and usage.

In the USA about two-thirds of superintendents apply generic pesticides to their golf courses, and about one-third spend half of their total chemical budget on post-patent products, according to a 2006 Golfdom survey of 495 superintendents. Of those who use generic pesticides, 93% say the primary reason is cost.

In 2006 we asked superintendents, what percentage do you plan to increase your generic fungicide use? Here's how they responded:

29.4% said they plan to increase usage by 10%, 16.7% said by 20%, 11.2% by 30%, 10.3% by 40%, 12.1% by 50%, 4.8% by 60%, 4.8% by 70%, 4.2% by 80%, 3.6% by 90% and 2.7% said they plan to increase usage by 100%.

The introduction of generic fungicides into the US turf market has followed on from generic herbicides that have been available for some time. According to the Golfdom survey of those who use post-patent fungicides, almost one-third spend at least 50% of their fungicide budgets on generic products. And trend data suggests they will use more each year if they believe generic products can perform as well as their name-brand counterparts.

Comparing generic chemical usage from 2004 to 2005:

6.4% of superintendents said they had increased usage by 100%, 5.2% said by 75%, 17.3% by 50% and 32.7% by 25%. 33.9% reported no change in usage. Only a very small percentage (4.5) said they had decreased usage by any amount.

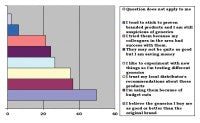

Nearly 50% said they believe generics are as good or better than the original brand.

From the above you would think that I am wholeheartedly endorsing the use of generics. That is far from the truth. Price, product support, and the actual distributor who sells the product are all factors that enter the "mix" when making a decision.

Whether manufacturers of generic or branded product, they all readily agree that, when purchasing product, you should buy from reputable dealers who are financially sound and agronomically strong, and it is this that will help maintain industry standards. While the products, formulations and results might be similar between branded and generic products, the service might not be.

For the vast majority of turf managers this means that, if you're used to being able to make a call into a company for guidance or diagnostic assistance, that there are only a limited number of companies in the marketplace who can actually provide the answers that you are looking for in a timely manner. Sure, there are plenty of companies who can supply product, but how many can actually advise how to use them properly?

Similar to consumer brand purchase decisions, trust, value and confidence are important factors when a turf manager makes a purchasing decision. While product cost is a consideration, it is not the only factor in the overall service cost.

If the comparison were as simple as lower price with no product support versus a higher price with product support, comparisons and buying decisions would be simple.

Making any purchasing decision solely on the basis of the supplier being able to provide technical support is not really practical, due to market considerations, as turf managers make any decision on the basis of four factors - effectiveness, long-term economy, the "social relationship" they have with the supplier and technical support.

However, the reality is that turfcare professionals now have a range of options that include buying branded products from the manufacturers or buying off-patent products from manufacturers of branded products.

The larger branded manufacturers do, however, give more than just product guarantees, as they also offer continuing education opportunities via product training seminars and sponsorships of professional association meetings. They are also the only ones conducting research and development, which helps build the foundation for future turfgrass maintenance programmes.

The counter argument to this is, does this justify charging higher end pricing for technology that is now regarded as being 'old hat'? Sure, charging top pricing for new technology as it comes online is all well and good, and perfectly justifiable, but how can it be justifiable for older molecules?

Significant opportunities exist for those generic manufacturers who can move from a complete reliance on price sensitive, commonly available active substances to the production of newly off-patent materials offered with additional services and guarantees of quality.