A walk in the park

Public parks are familiar to most people today either because we make use of them in our daily lives or because we played in them as children. Every town of any size has its public parks, gardens and recreation grounds.

They were created throughout Britain during the nineteenth century, and the first decades of the twentieth century, initially as part of the solution to the appalling problems of the urban environment brought about by industrialisation and rapid population growth.

They were created throughout Britain during the nineteenth century, and the first decades of the twentieth century, initially as part of the solution to the appalling problems of the urban environment brought about by industrialisation and rapid population growth.

As the population increased and towns expanded new buildings spread over the open spaces in and around cities. In the early decades of the 19th century the problems resulting from massive unplanned expansion began to become increasingly recognised.

The utilitarians, following the social ideas of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, stressed the need for action in order to bring about the greatest happiness for the greatest number. They believed that, by providing the 'green lungs of the city', it would help prevent the spread of disease by providing space to take exercise, opportunities to enjoy nature and greatly improve the overall appearance of cities and towns. Others remembered the French revolution and were aware of the growing working-class movements such as Chartism.

The creation of these 'people's parks' for the use of all urban citizens began at a time when there was no town planning and the structure of the local Government was only just evolving. By the end of the 19th century public parks has become an essential part of the urban fabric. The word 'municipal' was synonymous with pride in local powers and the ability to effect positive change.

The years 1830-1885 were the pioneering period of park creation. By the 1885 park development was assured and many more parks were created between 1885-1914.

The first public park in England was Regents Park in London, open primarily as a subscription park circa 1810 and then made into a public park in 1835.

The first public park in England was Regents Park in London, open primarily as a subscription park circa 1810 and then made into a public park in 1835.

The evolution of the first public parks took place in the North West of England. The people's park of Birkenhead was designed by Sir Joseph Paxton and completed in 1847. Prior to this public park landscaped gardens required an entry fee or subscriptions (except Regent Park) making public spaces available only to the wealthy.

Frederick Law Olmstead, designer of Central Park New York City ten years later, quoted on Birkenhead Park "All this magnificent pleasure ground is entirely, unreservedly and forever the peoples own. The poorest British peasant is as free to enjoy it in all its parts as the British Queen".

The design of the park was unique in that it had to be as transparent as possible, allowing the poor to gaze at the affluent merchants houses surrounding it, thereby reminding the former of their community responsibilities. The cost to create the park in 1847 was more than £90,000, plus an additional £80,000 for planting and excavation work, totalling £170,000, a colossal amount of money.

By comparison £11.3 million has recently been spent as part of the ongoing restoration scheme of Birkenhead Park.

After World War II the emphasis on town planning was, understandably, on slum clearance and urban renewal. New parks were not a priority in this planning process. After 1945 the influence of modernism extended and parks began to suffer from its influence. Flowerbeds were ripped out and replaced by large areas of grass.

One area of new park development in the post war period was in the 'new towns' that were created in the 1950s and 1960s. One of the main provisions being that parks and other open spaces should be included in the plans from the outset.

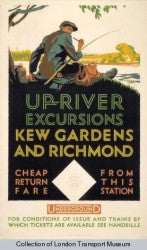

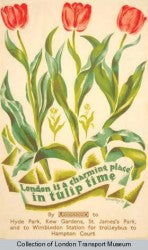

In the capital, London Underground designed posters to promote the use of parks and open spaces that were accessible by tube. The 'garden cities', such as Welwyn and Letchworth, were seen as a desirable place to live away from the smog of the city.

With an ever-expanding city, particularly post World War II, the need for open space in London and the Home Counties became an integral part of urban planning.

With an ever-expanding city, particularly post World War II, the need for open space in London and the Home Counties became an integral part of urban planning.

In 1934 The London County Council Green Belt scheme was launched. In order to reserve a supply of public open space for recreational use around London, it offered neighbouring county councils and boroughs up to half the cost of an approved land acquisition. The response was immediate. Within fourteen months, 28.5 square miles had been acquired in this manner and it's future was insured with the passing of the Green Belt (London and Home Counties) Act in 1938, which prohibited the sale and development of green belt land without the consent of the government and contributing county councils.

The reorganisation of local government in the 1970s merged the parks departments within leisure services, as was recommended in the Basin Report of 1972. This then led to parks competing with leisure services for an ever dwindling budget - and a budget for parks was not included in the government's standard assessment.

As parks maintenance is not a statutory responsibility, local authority budget cuts in response to pressure from central government, and the threat of rate capping if they overspent, has often fallen on parks.

A further factor promoting the decline of urban parks resulted from the Local Government Act of 1988. This required all services to be put to tender. Compulsory Competitive Tendering (CCT) meant that, instead of parks departments continuing to be responsible for their maintenance they became the clients.

In general, parks of historic interest represent 9% of the total number of open spaces and 32% of the total area. The total number of all parks, including recreational areas, exceeds 27,000 in the UK. Estimated number of visitors annually to historic parks is over 296 million, with an estimated 1.5 billion to all parks and open spaces.

In general, parks of historic interest represent 9% of the total number of open spaces and 32% of the total area. The total number of all parks, including recreational areas, exceeds 27,000 in the UK. Estimated number of visitors annually to historic parks is over 296 million, with an estimated 1.5 billion to all parks and open spaces.

In 1992 an audit commission sponsored a MORI survey on recreation. It found that, while 46% of people had used local authority leisure centres or swimming pools within the past 12 months, 70% had used parks, playgrounds and open spaces.

Today, local authorities are more 'switched on' to the benefits that parks provide. Whilst some still follow the CCT route, many have returned to using their own staff to tend these green spaces.

In March of this year, the Government announced that £1 million was to be invested into a UK-wide horticultural apprenticeship scheme, a move welcomed by the Royal Horticultural Society and other bodies.

It is estimated that some eight million people will visit a park on any one day in the UK and it is good to know that, once again, parks and open spaces are high on the agenda once again.

Author - Justin Grew

Poster images copyright of London Transport Museum