Bee Healthy, but Bee Wise...

"We believe that tackling the root causes of a problem is the most responsible way forward for us to take - just blaming the nearest chemical whenever there is a problem is not"

"We believe that tackling the root causes of a problem is the most responsible way forward for us to take - just blaming the nearest chemical whenever there is a problem is not"

Dr Julian Little, Communications & Government Affairs Manager, Bayer CropScience Limited.

Insecticides have been specifically designed to kill insects. Bees are insects. Therefore, all insecticides kill bees. End of story. Full stop. An entirely logical deduction but, equally, an entirely flawed one.

In reality, our ability to selectively control pests and diseases, whilst leaving other beneficial insects unharmed, combined with very strict regulatory controls to stop the use of unsuitable chemicals, and complemented with effective stewardship to ensure that people applying such products do so in the best possible way, has led to more food being available, more gardens looking the way the gardener envisaged, and more football pitches lasting the whole season, than ever before.

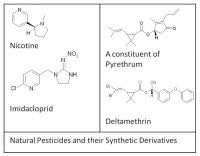

In nature, insecticides are not unusual. Chrysanthemums are well known for their ability to resist attack by insects by producing pyrethrum. A number of other plants, especially those of the genus Nicotiana, have evolved to resist attack from insects by producing chemicals which stop insects foraging on their leaves; the plants are better known as tobacco, and the chemical is a highly addictive natural product called nicotine.

In agriculture, insect damage is considerable, even in the UK - in the case of flea beetle in oilseed rape, yield losses, even in normal years, can be as high as 20%.

In the search for more effective ways of insect management, scientists have looked at natural products and attempted to improve upon them. Hence, natural pyrethrums were replaced by more effective new versions called pyrethroids. Likewise, scientists also looked at nicotine's mode of action. It was found that the "nicotine receptor" could be blocked by other nicotine-like compounds which were dubbed neonicotinoids. The advantage of both types of insecticide was their select effectiveness against certain insects in crops, coupled with a very low mammalian toxicity.

Running parallel to such scientific endeavours, the concerns about the indiscriminate use of insecticides, and pesticides in general, have led to a very sophisticated regulation system in the UK.

Regulatory Approval of Insecticides

Getting a new product to the market is extremely difficult, routinely taking ten years from the time that someone has observed that a compound has an effect on an insect, to the first sale of that compound. On average, the cost of doing so is £200 million, this having gone up by approximately 70 % in the last ten years. The success rate of bringing a product to the market is currently one in 150,000, down from one in 38,000 in the 1980s, and one in 10,000 in the 1960s; the vast majority of the cost and rate of success is a direct result of the need to test for, and satisfy the demands of ever increasing regulatory aspects for human and environmental safety. Some of the aspects to be investigated are highlighted in Box 1.

% in the last ten years. The success rate of bringing a product to the market is currently one in 150,000, down from one in 38,000 in the 1980s, and one in 10,000 in the 1960s; the vast majority of the cost and rate of success is a direct result of the need to test for, and satisfy the demands of ever increasing regulatory aspects for human and environmental safety. Some of the aspects to be investigated are highlighted in Box 1.

Whether or not a pesticide passes these tests is also a long process, involving an assessment by the European Food Safety Authority and an in-depth analysis to decide whether its use is appropriate within the UK. Essentially, all of the results are evaluated by government scientists at the Chemicals Regulation Directorate (CRD), a part of the Health and Safety Executive, who then make a recommendation to the Advisory Committee on Pesticides (ACP), a committee made up of independent medical, academic and other experts. By unanimous decision, this committee makes recommendations to Ministers who will grant an approval as appropriate.

So, in agriculture, those products which have a high intrinsic issue with bees are not normally allowed to be registered for use as a spray on flowering crops where bees will be foraging. On the other hand, they may be eminently suitable as a seed treatment, since beneficial insects such as bees will never come into contact with sufficient concentrations of the insecticide to pose any insect health issues. Hence, imidacloprid and clothianidin neonicotinoid containing products are used as agricultural seed treatments. Conversely, thiacloprid, which is a neonicotinoid with a very positive bee health profile, can be used as a spray in the field, even on flowering plants.

Thus, when Bayer CropScience developed Provado Lawn Grub Control to reduce the destructive presence of cranefly larvae and leatherjackets in lawns, the regulatory authorities will have reviewed the information and determined that, since this product was to be used on mown grass, where there are essentially zero foraging opportunities for nectar seeking insects, the use of imidacloprid was entirely appropriate.

Bee Health

It is clear that honey bee health is in serious decline in the UK, Europe and North America, and that this is linked with severe infestations of a parasitic mite called  Varroa destructor. Ironically, one of the best treatments for controlling this pest, up to now, has been a selective insecticide, such as Bayverol, a product produced by Bayer Animal Health. Unfortunately, in many cases, the Varroa mite has become resistant to this type of treatment, in the same way as some weeds become resistant to some weedkillers, and how some bacteria become resistant to some antibiotics.

Varroa destructor. Ironically, one of the best treatments for controlling this pest, up to now, has been a selective insecticide, such as Bayverol, a product produced by Bayer Animal Health. Unfortunately, in many cases, the Varroa mite has become resistant to this type of treatment, in the same way as some weeds become resistant to some weedkillers, and how some bacteria become resistant to some antibiotics.

In addition to Varroa, there are a number of viral and fungal diseases that are damaging bee colonies throughout the UK. Exacerbating this are other parasites, such as Nosema, which can reduce the lifespan of an infected young bee by nearly 80%.

While the decline in honey bee health is often billed as a global problem, there are countries that have relatively good bee health - Australia for example, which is free of Varroa. Countries that use the Africanised honey bee, rather than the European types, in Africa and South America, also have better bee health because the Africanised bee is better adapted to the presence of Varroa mites.

Neonicotinoid Insecticides and Seed Treatments

Despite being approved for use across the world as a safe and appropriate method for pest management when used as directed, some groups and individuals have suggested that the use of neonicotinoids, such as imidacloprid, in a seed treatment may have issues when it comes to bee safety.

So, what are seed treatments? They involve putting a layer of a pesticide on the surface of a seed, which then protects the seed and the young plant as it grows. Farmers prefer this to crop sprays because it is more effective, reduces the number of sprays, reducing the impact on non-target species inhabiting adjacent areas. All this has contributed to almost the entire oilseed rape crop in the UK being treated via its seeds.

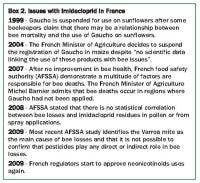

The argument against seed treatment with neonicotinoids stems from laboratory studies that show that low doses have an impact on bees. It extrapolates from such results that, although the insecticide will not kill the bee or colony outright, it somehow weakens the bee, or diminishes its overall health. Such arguments have, sometimes, put political pressure on policymakers in some countries to make rapid decisions without real scientific evidence, for example, in the case of imidacloprid in France (see Box 2).

The argument against seed treatment with neonicotinoids stems from laboratory studies that show that low doses have an impact on bees. It extrapolates from such results that, although the insecticide will not kill the bee or colony outright, it somehow weakens the bee, or diminishes its overall health. Such arguments have, sometimes, put political pressure on policymakers in some countries to make rapid decisions without real scientific evidence, for example, in the case of imidacloprid in France (see Box 2).

In reality, pesticide regulators are well aware of potential effects in the laboratory and, where they are found, further studies are demanded to determine what happens under realistic conditions in the field before such products can be commercialised. Likewise, it is important to note that the commercialisation of a product is not the end of the story - the updating of the regulatory files is a continuous process, and will take into account any new scientific evidence that comes to light.

So, in the case of this class of insecticides, there have been numerous tests done post-registration, including four large 'multifactorial' studies in the US, Belgium, France and Germany, in which all the possible issues concerning bee safety have been analysed under real field conditions. In all such studies, poor bee health correlates well with the presence of Varroa and bee diseases, but there is little correlation with the use of neonicotinoids.

This does not stop some people blaming insecticide use, of course, and recent newspaper headlines continue to put neonicotinoids into the spotlight. But, as one researcher whose work had been misquoted said in response to suggestions that his work definitely showed a link between bee health and insecticide use, "It is not possible to make a direct comparison with a lab study and what might occur in the field," and that the results "do not provide a direct link to [bee] colony losses..."

This does not stop some people blaming insecticide use, of course, and recent newspaper headlines continue to put neonicotinoids into the spotlight. But, as one researcher whose work had been misquoted said in response to suggestions that his work definitely showed a link between bee health and insecticide use, "It is not possible to make a direct comparison with a lab study and what might occur in the field," and that the results "do not provide a direct link to [bee] colony losses..."

Conclusion

Bee losses are occurring in both the UK and elsewhere in the world, and their root causes have to be managed to safeguard this economically important pollinator. Whilst bee losses do not seem to correlate with the use of insecticides, farmers should handle them properly; indeed the industry has recently launched a campaign highlighting the need to "bee careful" when using insecticides for any reason. Likewise, companies such as Bayer CropScience have recently announced joint research programme with Bayer Animal Health to bring to the market new products to control the Varroa mite, a basic tool to manage bee health in the UK.

We believe that tackling the root causes of a problem is the most responsible way forward for us to take - just blaming the nearest chemical whenever there is a problem is not.

With thanks to Dr Julian Little, Communications & Government Affairs Manager, Bayer CropScience Limited.